At what point did art criticism become more about Rousseau than about Rembrandt? That’s a rhetorical question: artists, and those who write about art have long tended toward a left of center bent, but of late much of what passes for criticism does not seem to be about the art at all, or at least not about art as an end in itself or of its structural relationships or how it achieves an emotional effect, but more about what it signifies in terms of a defined version of social consciousness and to what extent art furthers the ultimate triumph of societal perfection.

I came across a piece in the New York Times: ‘Hamilton,’ ‘The Simpsons’ and the Problem With Colorblind Casting, by Maya Phillips, July 8, 2020. Now perhaps a bit dated but I think still cogent to my purpose. The following is not intended as a review: I use several of Ms. Phillips’s points as a springboard to a discussion of the angst ridden landscape of contemporary cultural assumptions, and to have read her article is not a prerequisite for following my argument, but rather some general familiarity is sufficient with the current lines of intellectual demarcation in the ongoing debates over affirmative advancement of minorities, the rights of cultural minorities to control over their cultural content, especially as applied to artistic expression, and the responsibilities of artistic expression to the ideal of ‘social justice’.

“Late June brought news that the animated shows ‘The Simpsons,’ ‘Family Guy,’ ‘Big Mouth’ and ‘Central Park’ would recast characters of color who have been played by white actors.” I am not sufficiently familiar with those programs to comment on the specifics of those decisions. But my first reaction was, on the face of the essay, to say to myself, how unjust, under the broad mandate of ‘social justice’, to remove talented actors, who have spent years developing elements of character representation, because of their playing roles, in blackvoice, not corresponding to their race—of a nominally anti-racist, but racistic exclusion of their fundamental function, as actors, to portray characters not themselves.

To begin with terminology, there is a difference between “colorblind casting” and casting that makes an artistic point of ethnic, racial, or gender optionality of casting and of ‘color forward’ casting where preference is given to minority actors. For Ms. Phillips’s examples, the disembodied voices behind the animations will be presumed to have been the result of colorblind casting, that casting decisions were made on the basis of the actors’ vocal abilities to enact scripted characters, regardless of their off-mic characteristics. By contrast, the casting of Hamilton, far from colorblind, successfully uses racial dislocation as a conveyance of transcendence, though for Ms. Phillips, the play may be criticized for ignoring the opportunity to expand its conception to encompass an exposition of slavery.

Ms. Phillips suggests that “colorblind” is often a guise for not accepting an obligation to aggressively cast minorities to roles which they might conceivably fit. While such forward leaning, affirmative casting may have good intention (disregarding questions of injustice done to one in the interest of justice for another), in practice such decisions may come down to artistic judgements of who of the available pool of talent best may suit artistic purpose. Exceptional talent is not available to be taken off a shelf, and exceptional is defined by a paucity of equivalencies. If there are equivalents of say Sir Laurence Olivier, whether white or black, at any particular moment, they will likely have previous commitments. And to the argument of the lack of narrative necessity, such as would invite the insertion of a person of color to a role in which the audience would not expect them, there may result a diminishment of verisimilitude. For the artist, verisimilitude, in the service of creation, may trump generalized goals dictated by doctrines of social consciousness. And the creation of a miasma, wherein creative judgement may be stifled by arbitrators of social justice, smacks of a censorship of artistic license, especially when the question is in the form of a negative, as in, “Why could that part not have been played by a person of color?”, requiring a rational justification of an intuitive process. It is possible that social justice may not have been the ultimate aim of the project, which, of course begs the question of why was it not. Which in turn raises the specter of Soviet-like interpretations of art as having a higher social function than as a legitimate end in itself: the assumption that art has a duty corresponding to a predefined social agenda, and the corollary that it is the role of the critic to examine the degree to which the artist meets that criteria, over and above that of being an analyst of what was formerly understood as artistic merit, i.e., the techniques the artist employs to achieve his self-appointed purpose and his degree of success in fulling that purpose, and the extent to which the creation stands as an end in itself. The critic becomes the arbiter of a politically defined version of social utility rather than of artistic merit.

Ms. Phillips says:

But however well-intentioned, there are complications that come with works that aim to use colorblind casting to highlight people of color who wouldn’t otherwise be represented. Creators may cast blind, thinking their job done, failing to consider that a black man cast as a criminal or a Latina woman cast as a saucy seductress — even when cast without any regard to their race — can still be problematic. One kind of blindness can lead to another.

Indeed, imagine that a black man might be blindly cast as a criminal, or a Latina as a saucy seductress: a blind criminal leading a blind saucy seductress—It has potential!

Contrary to the trend toward cultural balkanization and the sanctity of those self-defined spaces, everyone, and especially every artist, in the interest of a pluralistic collective in which all may flourish within a nuanced milieu of cultural exchange and integration, should be free to channel their inner black person, inner Jew, inner Crazyhorse, his inner woman (and vice versa). They are all our rightful selves to the extent that we have empathically embraced them and that they are all expressions of our convoluted ancestry, relationships, experiences, and common human nature, i.e., of our integrated selves within the broader cultural milieu.

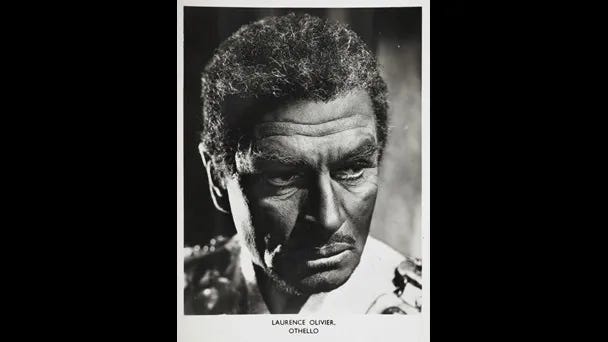

Everything an actor or a writer does is some form of appropriation or approximation. How can it be wrong for Olivier (yes, in blackface) to play Othello when the character was imagined by a white guy from Stratford in a time and place where blacks hardly existed other than as fictional stereotypes. And if you might grant, for the sake of argument, that there is also justice in choosing the actor solely on the basis of merit, or to the judgement of the author or director of who might best suit his artistic purpose, Olivier, in this case, would look rather unconvincing without his makeup. It would seem not too much of a reach to presume that the director of the London presentation of 1964 was aware of the tension of a white actor in a black role—that it served to underscore the isolation of a foreigner, signified by his blackness, in the white man’s insular world of Elizabethan England, or of the evolving racial complexities of the time of its modern recreation. It is interesting that Olivier, in contemporary promotional photographs, looks the part of a North African Moor more convincingly than other prominent actors of sub-Saharan characteristics who have also successfully played the role.

Or should the author, rather than the actor, not be more soundly blamed for the audacity of his attempt to understand and portray the form of a black man’s character? And that is not the only example of Shakespeare’s audacity of appropriation or of his presumption of knowledge beyond his direct personal experience. He did the same with women, presuming to know Ophelia’s inner feelings or how Lady Macbeth might have ambition and a courage beyond the stipulated boundaries of her sex. And he cast young men to play them. Most of the comedies are dependent on disguise and confusion of sexual roles—much painting of faces. And he used imagination to explore the worlds of those above his own station or beyond his experience; he never went to war or saw the Mediterranean. How would he know the character of a King Lear or understand Hotspur’s sense of honor when himself but an actor and a scribbler?

One may imagine that this current trend of cultural exclusivity, if to run its course to its logical conclusion, would result in authors writing scripts in which all the characters are of their own racial or ethnic identity engaged exclusively in same sex relationships or in totally deracinated artistic landscapes devoid of any pluralistic overlapping of cultural richness or innuendo. Does this sound Orwellian?

Did I miss something? I thought appropriation and approximation were what actors and authors did: to imagine one’s self another, to pull an accent from a foreign tongue, to paint one’s face, to engage the limits of imitation to the point of enlarging the representation beyond the boundaries of the script: to know the subtle meaning an expression might convey to better speak the meaning of the written word. How is it that a modern Yankee white woman can play a 19th century Southern belle but not a Southern slave? Are not the journeys somewhat comparable in terms of commonalities of human nature and the relative distance the actor must traverse? Is race the bridge too far? Or a bridge to be drawn up in defense of the citadel of identity politics? Is there not a convergence of contradictions between the critique of traditional assumptions of artistic license and of Drag Queen Story Hour?

Can a race or ethnic group own a special place of experience that is just its own, an island to itself, inaccessible to those who have only the tools of intelligence, and empathy, and their own broad experiences with which to make the journey, those who, driven by ambition, talent and insight would be a bridge to a broader understanding? Is there a fundamental difference in the nature of human emotion from one race to another, or, in pursuit of an understanding of one’s own experience, can an author or an actor not discover authenticity through an honest attempt to penetrate the barriers that make another’s experience a private place, that the attempt may have of itself an authenticity: for surely storytelling, as opposed to journalism, is as much about what the artist brings of himself as it is to what the story is nominally about, authenticity as much a judgement of the finished product as it is of accuracy of the observation—that an artistic representation may have a truth within its own established universe, while not violating the journalistic standard of a truth well told. Fiction may lead to deeper penetration by virtue of its detachment from literal truth. An outsider, by virtue of being an outsider, may bring a detachment of perspective that even a native of that place must similarly attain in order to be able to export an interpreted experience, on a two-way street, beyond the strictly personal or culturally situational. Both authors, coming from different places, seek to approximate closely encountered realities, whether ‘lived’ or observed, to a transcendent artistic application so as to gain the empathetic response of a wider audience for portrayals of intimate circumstances that touch broader environs. Communication between communities requires a common language of abstracted experiences nurtured by an interactive exchange of cultural DNA.

Othello, the play, in Shakespeare’s presentation, is not about race; rather race is used as a devise to emotionally isolate the character, which would presumably have been played by a white actor in blackface, that in itself at the time a given of no special notice. Olivier’s Othello, on the other hand, would have been played, to a sophisticated London audience in 1964, attuned to the contemporary heightened awareness of racial injustice, especially as being played out in the American Civil Rights Movement. Audiences would have empathetically internalized the transfiguration of the great Shakespearian actor of his time, actor and character reaching an apotheosis of unity, the former in the skin of the latter, and the dramatic emergence of everyman—integrated in the sense of the spiritual emergence of the empathetic commonality that transcends our narrow boundaries, our restricted identities, of all that would deny empathetic compassion. The racial integration of actor and character would have been substantive to the role.

It has been stated and implied that because of inherited guilt whites have no right to assume insights into black American culture—a distinct and separate thing from white American culture—except as they may be redemptively informed by black missionaries from the interior as to the reality of the black experience. The current emphasis of the civil rights movement would seem to have shifted from a goal of cultural integration to one of the solidification and mobilization of a power base built upon identity, and no small amount of counter-racism, when what is sorely needed, and what would better serve the common good, would be more efforts of coming together in a spirit of empathetic understanding. The efforts of a minority interest (blacks represent 13.6% of the U.S. population.) to maintain a cultural identity apart, and contradictive of the ideal of a broader social consensus, is ultimately counterproductive and unsustainable, which is not to deny the importance of identity consciousness within a pluralistic society. But ‘separate but equal’ was never either a just or practical solution; such concepts of divisibility would be better termed ‘separate but in perpetual conflict’. And that formulation is no more tenable today than it was at the time of the Civil War or of the Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954. Is it not something of a conceit to think that a racially defined cultural exception may be maintained within the public space?

This of course relates substantially to the perception and reality of white racism today, the artefactual remnants of what was once a largely impenetrable barrier, but more particularly to the legacy of white guilt that exists separate from that now disjointed and slowly fading reality. Those deep layers of compacted guilt are mined to profit by those whose intellectual fortunes are founded upon fixed visions of victimhood and entitlement, and who insist that the progress of the last six decades—the dismantling of legal, political and social barriers—is ephemeral, only serving to divert attention from an invisible conspiracy to keep the black man down. White racism certainly continues to exist, but hardly as a unified edifice. Within the professions, within liberal (and illiberal) intellectual circles, and within the arts, the shoe seems now as often on the other foot.

A note on capitalization: In the interest of societal integration of diverse groups, I support the decapitalization of both identity assertive ‘Black’ and the reactionary ‘White’, as barriers to meaningful integration, as emphasizing boundaries where the gradual diminishment of such divisions would better promote opportunity ,i.e., true justice, for all. If race is but a social construct, as some have argued, it is underserving of formal distinction. If, on the other hand, race is real but those distinctions weakening over time within breeding populations, and meaningful integration a goal, the recent introduction of capitalization to indicate somewhat arbitrary usage on the basis of self-identification along a greyscale of an increasingly mixed-race population seems counterproductive, burdening those terms with more intractable distinction, so would serve those who would make words sharp weapons of symbol warfare.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Perfect Circle Press to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.